Imposter syndrome

I wrote this story in a rush of enthusiasm last spring after an incredible Signal exchange with its protagonist, whose name I’ve changed. I was at NICAR 2020 in New Orleans at the time and remember being distracted from whatever talk I was in by the messages popping up on my phone.

That conference turned out to be a probable super-spreader event for the then-novel coronavirus, and due to a shift in strategy the piece no longer works for my day job, so I present it here. It’s based on a few snippets from the 29Leaks data set, offering a glimpse into the murky origins of the crypto-currency exchange BTC-e, which imploded spectacularly in 2017—I’ve been following the story ever since.

This piece takes some knowledge of BTC-e and its downfall for granted—for a quick primer, try this RFE/RL story.

The email was short and to-the-point:

I am an attorney. One of my clients requires fast company formations with bank accounts or ready-made companies with bank account. Jurisdiction doesn’t matter a lot. Can you provide me with full list of available variants and solutions?

Best wishes,

Ivan Kuznetsov

For Oliver Hartmann, the request wasn’t out of the ordinary. Working for Formations House—a ‘company mill’ based in a grand townhouse on London’s Harley Street—he was used to providing clients with shell companies at short notice and with very few questions asked.

The service was attractive to criminals. Companies sold by Formations House would go on to be involved in fraud, corruption and organised crime connected to everyone from the Italian mafia to the Iranian state oil company. Kuznetsov’s client was no exception—new evidence suggests that they may have been one of the operators of BTC-e, a notorious crypto-currency exchange shut down by the FBI on money-laundering charges in 2017.

Hartmann wrote back the same day with an offer: a company with the deliberately bland name UK Business Consultants Ltd, complete with a two-year filing history to make it appear more legitimate and a functioning Barclays bank account. The package would cost £6,000 in total—Kuznetsov agreed. Unbeknownst to each other, both parties to the deal were lying.

According to a Pakistani newspaper, Hartmann’s real name was Syed Rizwan Ahmed and he was writing not from a plush office on Harley Street but from a business park in Karachi, doing work outsourced by Formations House to reduce costs. Kuznetsov used his real name, but far from being a high-powered lawyer, he was in fact a 16-year-old operating with little more than an email address and a cheap website.

How did a teenager from Moscow end up buying a British company for international criminals involved in a high-tech money-laundering conspiracy? And what does it say about the UK’s system of corporate registration that he could?

View from the embankment next to Gorky Park (flickr/@deepgoswami)

Teenage dreams

Ivan Kuznetsov was born in Moscow in the late ’90s and attended an elite private boarding school in a leafy neighbourhood near Gorky Park. It is the school’s address that he gives in correspondence with Formations House, and in registration records for website domain names.

Kuznetsov appears to have started working as an ad hoc company formation agent in 2013, maintaining two interchangeable brands: “OffshoreIt” and “Incorporatio”. The website for the latter was light on detail but promised a slick service: “Painless incorporation in 19 jurisdictions. In a few clicks.” Customers were encouraged to fill out a form or to contact the company directly via email.

To drum up business, Kuznetsov posted on web forums devoted to making easy money. With names like Money Maker Group and Dark Money, these Russian-language bulletin boards ranged from innocuous chat to open discussion of fraud and financial crime. The latter, which until recently advertised itself under the slogan “Everything can be cashed out!”, provided a bustling marketplace for scammers, fraudsters and would-be criminals, offering each other tools and techniques for converting assets obtained through cyber-crime and other means into ready cash.

It was likely through one of these forums that Kuznetsov came into contact with the men behind BTC-e. Alexander Vinnik, one of BTC-e’s alleged operators, was known to post on similar sites under the username “WME”, offering under-the-table money exchange services. His careless posts, sometimes giving away crucial information such as his real name, will have formed a substantial part of the evidence used to indict him in the United States, leading to his arrest and an extradition battle that has dragged on for more than two and a half years.1

When contacted, Kuznetsov said he couldn’t remember exactly which forum he had been approached through, but that the client had introduced himself using the name Mikhail. The conversation quickly moved to the instant messaging service Jabber, which is popular among cyber-criminals, and discussions continued for “about a month” before Mikhail paid for the company.

Public records show that Kuznetsov and Vinnik both held accounts on the Money Maker Group forum—Kuznetsov joined on 8 December 2013, just five days before he contacted Formations House, prepared to purchase a ‘ready-made’ company with a bank account attached. Another candidate for Kuznetsov and Vinnik’s virtual meeting-place is the Migalki forum, which Kuznetsov says he used regularly, and which shut down in 2014. “Migalki” is a Russian term for flashing lights affixed to the cars of high-ranking officials—as well as their corrupt cronies in the business world—allowing them to cut through traffic.

A screenshot of Kuznetsov’s website

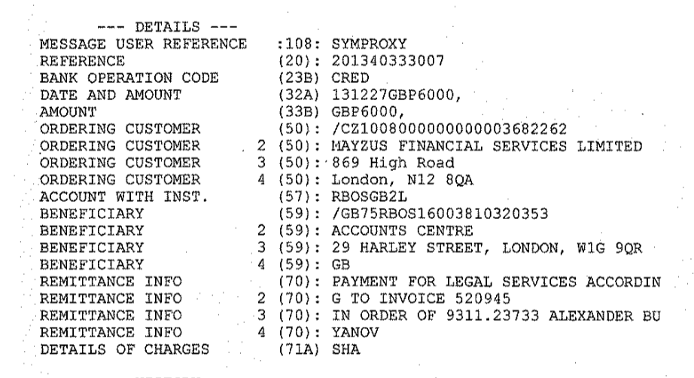

Kuznetsov says he was unaware of the real identity of the man who introduced himself as Mikhail, and he was careful not to give away details in his conversations with Formations House, but a strong link to Vinnik can be established through transaction records. In order to prove that the £6,000 fee for UK Business Consultants Ltd was on its way, Kuznetsov sent a printout from the SWIFT payment system. Dated 23 December, it shows a transaction from Mayzus Financial Services (MFS)—a Czech-based payments company described by the FBI as having “significant financial ties to BTC-e”—to Formations House, with the following payment reference:

PAYMENT FOR LEGAL SERVICES ACCORDING TO INVOICE 520945 IN ORDER OF 9311.23733 ALEXANDER BUYANOV

In a letter to MFS shareholders following the collapse of BTC-e, CEO Nikolay Rozhok described payment accounts that the company had opened at Vinnik’s instigation. Among them was one under the name Alexander Buyanov with the account number 9311.23733—the same as the one listed in the payment reference.

In 2016, Buyanov—a DJ at a Moscow karaoke bar—popped up again, registered as a ‘person of significant control’ in relation to a UK company called Always Efficient LLP. Listed on BTC-e’s website, this company appeared to be investigators’ best shot at finding out who was behind the exchange. But when a Russian journalist tracked him down, Buyanov claimed he had never heard of Always Efficient. Either his identity had been hijacked or he was a willing ‘cut-out’, put in place illegally to shield the company’s real beneficiaries.

SWIFT transaction details for a 23 December 2013 payment to Formations House

The Baltic connection

Buyanov wasn’t the only seemingly unrelated figure in the byzantine corporate structure behind BTC-e. In order to purchase UK Business Consultants Ltd, Kuznetsov and his client had to provide a director who could be registered with Companies House—one who wasn’t connected to the company’s real owners and beneficiaries.

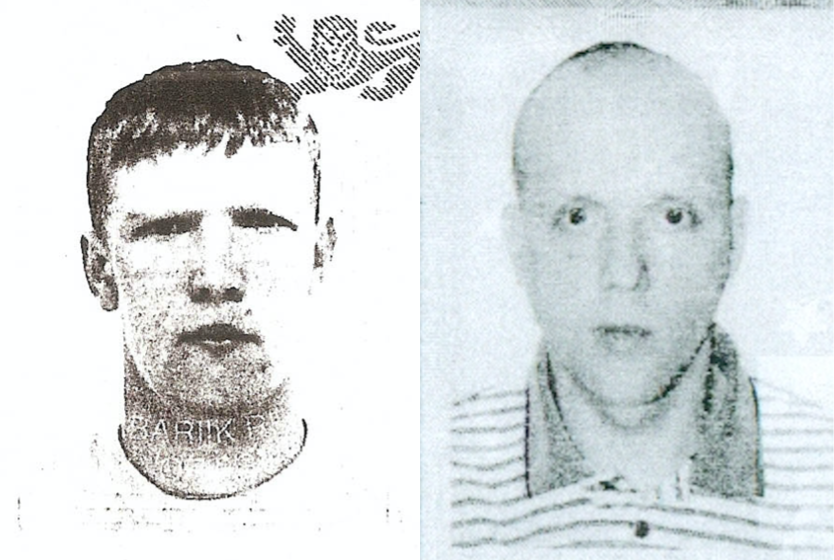

The first candidate was a 36-year-old Estonian man called Vladimir Nikulin. Having paid for the company, Kuznetsov sent over proof of identity and address for Nikulin and arranged for him to visit the Formations House offices on Harley Street on 10 January 2014 to sign the relevant paperwork. But as a series of increasingly confused emails between Kuznetsov and Hartmann attests, Nikulin never showed up.

The following week, Kuznetsov wrote to Formations House with an apology: “I am writing to say that I and my principals […] became a victims of fraud on the part of man, who introduced himself as Mr. Vladimir Nikulin.” According to Kuznetsov, Nikulin—who had introduced himself as a professional nominee—took payment of $1,800 for his services, but provided forged documentation and had now stopped responding to emails and phone calls. Kuznetsov received a response from Formations House’s owner, Charlotte Pawar, who advised him to seek a new nominee director.

The second attempt was more successful. Kuznetsov’s client provided him with details for Jurijs Belovs, a 39-year-old builder. Like Nikulin, Belovs hailed from the Baltic—Latvia rather than Estonia—and belonged to his country’s sizeable Russian minority. As Russian-speakers, both men could communicate easily with Kuznetsov and his clients, but as citizens of European Union member states they could also travel freely to the UK, making them ideal nominees for British companies.

This time, Kuznetsov’s clients didn’t take any chances. Belovs was accompanied to the UK by a translator, who Kuznetsov claims was “probably his minder as well”. After flying into Heathrow Airport on the morning of 3 February, Belovs made his way to Harley Street and Hartmann—actually writing from Pakistan—confirmed his arrival: “Yes, he is here. And the process is ON”. Once appointed, Belovs remained a director of UK Business Consultants Ltd until the company was struck off for failing to file accounts in September 2015.

After an extensive search, I was unable to contact Vladimir Nikulin, and Jurijs Belovs did not respond to requests for comment. There is no suggestion that either man knew the probable identity of Kuznetsov’s clients or that they were otherwise involved in the operation of BTC-e.

Passport photos of Vladimir Nikulin (left) and Jurijs Belovs (right)

Passport photos of Vladimir Nikulin (left) and Jurijs Belovs (right)

Too easy?

These days, Kuznetsov is on the right side of the law. Since 2016 he has worked in compliance, helping companies in the EU financial sector obtain regulatory licences. He looks back on his offshore dealings with embarrassment, but they have at least given him an insight into how criminals seek to circumvent money-laundering regulations.

One jurisdiction stands out. “It is astonishing that UK govt doesn’t give a damn about what’s happening with corporate registrations,” Kuznetsov said. “If you look at the [Money Maker Group] forum, you would find hundreds of ponzis [fraud schemes] which have UK registered companies”.

His claims are backed up by the evidence. Research by Global Witness in 2019 found that the UK’s beneficial ownership register—introduced in an attempt to combat criminal and fraudulent use of British companies—isn’t being implemented properly. Despite registration being compulsory, the data is incomplete and filled with inaccuracies.

This time last year more than 330,000 companies declared that they had no beneficial owner, 487 were part of circular ownership structures and several were apparently controlled by children under the age of two. The situation isn’t much better across the EU, where implementation of beneficial ownership registers remains patchy, despite being required by law.

Sitting behind many of the abuses of UK companies is Formations House. Research by the The Times and the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, using the same data as this article, found that companies created by the formation agent had been associated with “vintage wine frauds, fake stock market tipsters, dodgy gold and diamond traders, overpriced land investment schemes and a Hollywood heist carried out by a bogus aristocrat.” Pawar, the company’s owner, was caught in a sting advising an undercover journalist on how to get around money-laundering rules.

In his dealings with Formations House, Kuznetsov found the company’s connections within the industry particularly attractive: “I am generally impressed with ties Formations House had with local UK banks,” he said. “Even back in 2014 it was highly unlikely that a company could be transferred [from its original owner] with banking relationships to someone who is obviously not a real director.” It was a service that Formations House was only too happy to provide.

While Kuznetsov has left the offshore world, a successor to Formations House is still in business. The company is now part of The London Office, a provider of virtual office services. And while it no longer offers companies with bank accounts attached, its roster of ‘ready-made’ companies is still deep. At the time of writing, Biz Consultancy Ltd, incorporated in 2003, could be yours for just £5,000. What you do with it is up to you.

Speaking to The Times in the wake of the 29Leaks revelations, Pawar provided this general statement:

Ms Pawar, 39, who heads the company from a home in Marylebone, central London, said that the database had been “stolen” from its server and used for “several reported extortion attempts”. “Like all other formation agents in our industry, we have no control over the actions of companies and their directors after we have provided our formation service,” she said. Ms Pawar said that her business carries out due diligence practices required by Revenue & Customs and performed more due diligence and anti-money laundering checks than were required by Companies House’s own online company formation process. “As part of our MLR [money-laundering regulations] registration we are required to carry out regular reviews of our compliance procedures. As a result, from time to time we have added new measures to our processes,” she said.

She also responded specifically and at length to the reporting of the undercover sting.

-

Vinnik has now been sentenced and is serving five years in France. ↩